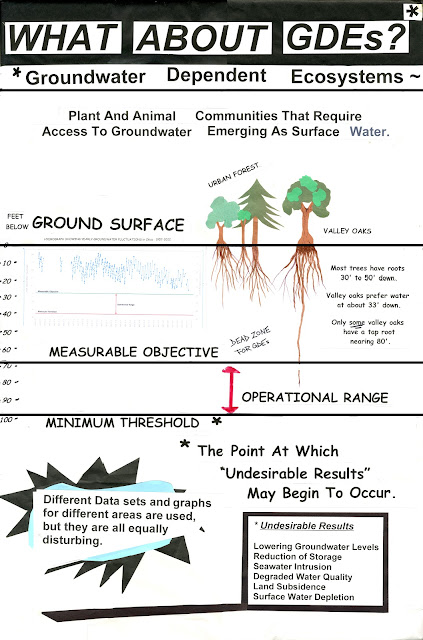

"Measurable Objectives" and "Minimum Thresholds" are terms from the State Groundwater Management Act's (SGMA) requirements. They create what is deemed an acceptable range of groundwater table levels. The Vina Groundwater Sustainability Agency, set up to manage SGMA compliance in the area that includes Tuscan Water District, has put that range below the level that will sustain urban forest and valley oak ecosystems, as well as countless wells.

It is false for anyone involved in these multiplying agencies to assert that they act independently of one another. They were created and are led by almost entirely the same group of people, linked together with tight family and business connections, and in control of all the levers of government in Butte County.

Read on for a detailed explanation of how geology and ecosystems relate to the battle over groundwater control.

The Tuscan Aquifer: A Leaky Bank.

An aquifer is an underground geological structure in which water is found, some at shallow depths, and more far below the surface. Aquifers are dynamic: Their levels rise by precipitation and percolation, creek and river flows, and seepage from aquifers at higher elevations. They sink due to pumping and onward seepage to lower elevations or deeper rock formations.

THE DARKER COLORS INDICATE LESS POROUS GROUND. TUSCAN'S NATURAL RECHARGE COMES MOSTLY IN THE VOLCANIC-ROCK FOOTHILLS.

Illustration from a Chico State study shows the complexity of soil porousness atop the Tuscan Formation west of Chico.The Tuscan Aquifer lies in a complex weave of soil and volcanic rock, the Tuscan Formation, which extends along the eastern Sacramento Valley from about the Thermalito Afterbay north toward Red Bluff.

This formation – which crops out east of Chico in the visible form of buttes – dips beneath other sediments of the Valley and reaches a depth of about 600-900 feet below the surface in Glenn and northern Colusa Counties, west of the Sacramento River.

While water seeps into it from most everywhere when rain is plentiful, the dominant flows originate in the eastern foothills and in the beds of southwest-flowing streams. (Some of these flow imperceptibly underground even when dry at the surface.)

The water seeps under the City of Chico, then onward under the valley floor where it props up shallower groundwater pools beneath Butte County’s vast orchards.

Because Tuscan groundwater levels originate in this elevated foothill zone, the water gets pressurized on its downward slant toward the west. This is why wells in the Butte Basin (south of the Vina subbasin, over which the TWD is mapped), and in eastern Glenn and Colusa, used to be artesian – the water pressure forced it upward.

WHY VALLEY'S EDGE MATTERS

Because the Tuscan formation sinks hundreds of feet below the Sacramento River, its depletion at deep levels, along with sharply reduced water flows into the river’s basin from Glenn and Colusa Counties, inevitably reduce deep-water pressure on our side of the river.

Click here to view Glenn County’s maps of dry well reports.

The Vina Subbasin portion of the Tuscan Aquifer underlies the City of Chico and much of the agricultural land to its north, west and south. Vina provides domestic water for about 120,000 people – but all those showers, dishes, and lawns use less than 10% of what is pumped in any given year. The rest is consumed by agriculture (a small percentage of irrigation water percolates back into the ground).

Our Tuscan Aquifer groundwater is still of very good quality, and if managed conservatively, can provide our area indefinitely with abundant agriculture and healthy ecosystems. Compared to the depleted, contaminated groundwater stranding more and more homes and communities with dry wells in the southern San Joaquin Valley, we have a precious treasure.

But long before drilling and pumping reaches the bottom of this ancient natural inheritance, the costs of over-pumping are coming into view.

The trees and the shallow domestic wells will be left high and dry first.

Valley Oaks: Canaries in the Coal Mine.

Valley Oak riparian forest currently occupies about 12,000 acres (4,856 ha) on the Sacramento River System, approximately 1.5 percent of its original acreage. These remaining valley oak riparian and woodland areas protect intensively used, critical wildlife habitat.

The trees are resistant to short-term drought; mature trees suffer drought damage only when a series of dry seasons lowers water tables to extreme depths. But Valley Oak have died out in many areas because of greatly lowered water tables.

The Vina GSA's groundwater sustainability plan is tied up in court because it explicitly tolerates groundwater depletion to levels that would certainly wipe out most if not all of these trees, and the habitats they support.

Overdrafting: Too Much Pumping, Not Enough Recharge.

The nearly 100,000 acres of land planted mostly with thirsty nut crops to the north, west and south of Chico are also irrigated almost entirely with water pumped from the Vina Subbasin area of the Tuscan Aquifer. Excessive pumping at any point can depress the water table elsewhere in unpredictable ways, and in fact, is already doing so.

According to Davids Engineering in their report Sacramento Valley Groundwater Assessment Active Management – Call to Action:

“...The ultimate effects of pumping can occur significantly after pumping starts, or even after pumping has ceased. The timescales involved in aquifer responses to pumping and other stresses can be on the order of decades, making it difficult to associate cause with effect. As such, monitoring must account for this lag in impacts. In general, the longer the timeframe for effects to be observed at a given monitoring point once they become evident, the longer those effects will persist, even if the pumping causing the effects is halted immediately.”

The numbers can vary widely. For the water year ended September 30, 2021, for example, about 268,000 acre-feet were pumped out while the depth of the current drought saw nature only give back an estimated 175,000 acre-feet. This implied an unsustainable 93,000 acre-feet shortfall.

However, with the exception of CalWater data, the estimated amounts of water in and out of the aquifer are unreliable and variable due to the complexity of the geology and flows.

The Vina GSA’s plan fails to model inter-basin leakage from the Vina into the Butte and Colusa sub-basins.

According to a July, 2021 report in the Chico Enterprise-Record,

“In an average year about 250,000 acre-feet (are) pumped in the Vina area, compared to about 150,000 acre-feet elsewhere in the county, according to data developed by the county Water and Resource Conservation Department.

Most of that goes to water the almond and walnut trees that are the primary crop in the Vina area. Chico’s water use is less than 20,000 acre-feet per year, according to the California Water Service Company’s 2020 water quality report for the Chico Division.

In dry and critically dry years, water use in the county has jumped about 100,000 acre-feet. Part of that was growers in the southern water districts supplementing reduced surface water supplies, but more than 80,000 acre-feet of the increase happened in the Vina Subbasin, according to the county’s figures.”

Recharge schemes are focused on spreading water throughout the valley floor. But a Butte County study shows that the aquifer’s natural recharge and depletion mechanisms call into question whether recharge schemes can reliably do any good.

River and stream leakage from the west contribute natural recharge to the Vina Subbasin’s shallower layers from the west, while the deeper layer – the Lower Tuscan Aquifer – is replenished by rainfall in the foothills and upper watershed (including the massive patch of land set to be developed as “Valley’s Edge.”)

The Deepest Pools Prop Up The Shallower Ones.

The pressurized deep Tuscan Formation prevents the overlying shallow Tuscan water from leaking downward. Aggressive pumping of the Lower Tuscan would allow the upper (shallow) Tuscan to decline. While this may create storage space for experimental replenishment programs, it would strand domestic wells, streams, oak woodlands and the Chico Urban Forest.

Researchers at Chico State University have studied the Tuscan Aquifer in depth. To quote the study:

According to the February 22, 2023 issue of the Sacramento Valley Mirror, the new president of the Glenn Colusa Irrigation District, John Amaro, stated, “The district is going to depend more and more on groundwater…”, describing it as a delicate and challenging issue given the impact of groundwater depletion on domestic wells in the county. The Mirror reported, “With groundwater projects on the drawing board, Amaro said he believes the right groups and people are involved to make progress on groundwater sustainability.”“Although the upper Tuscan Formation houses the main groundwater supply for portions of Butte, Glenn, and Tehama counties, years of relatively low precipitation in the Sierra/Cascades and the local foothills have stressed groundwater levels causing many irrigation districts to rethink their projected water allotments.

In 2006, the Glenn Colusa Irrigation District (GCID) and the Natural Heritage Institute (NHI) jointly embarked on an investigation to explore how Shasta and Oroville reservoirs could be re‐operated more aggressively in conjunction with the lower Tuscan Aquifer to increase water supplies.

“Improve Central Valley system-wide water supply reliability through participation in the emerging water transfer markets…The Lower Tuscan Formation, if integrated into California’s water supply system, could provide major water supply reliability benefits… it will take decades before we know enough about the aquifer dynamics to devise… a risk- free regime, and yet it would be foolish to require that the aquifer remain an underperforming asset in the interim... The rapidly emerging Central Valley water market and unpredictable climate amplifies interest in producing groundwater from the “Tuscan Aquifer System”.

Of course it does.